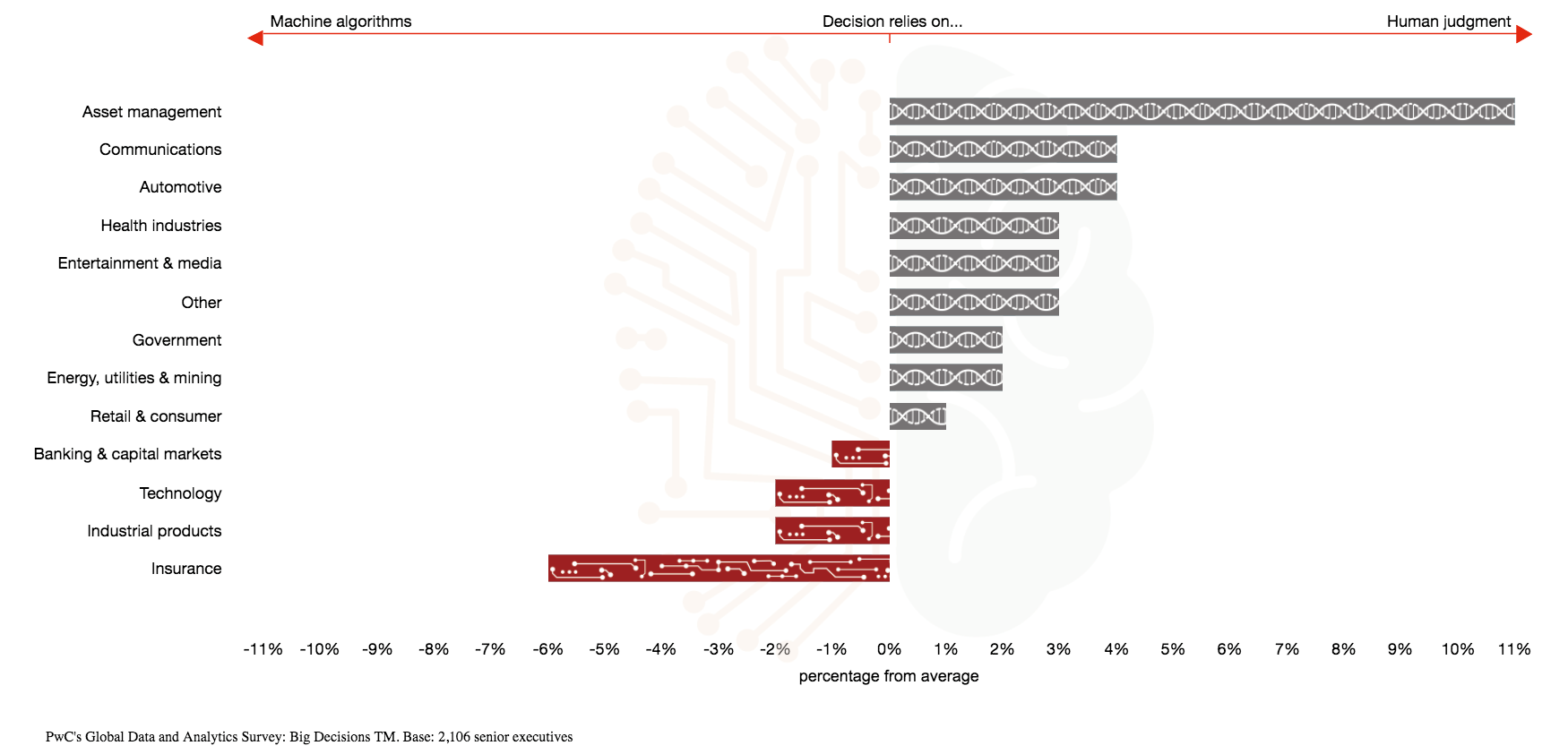

In my reading, I came across this chart not long ago which is profoundly revealing:

PricewaterhouseCoopers did a global survey in 2016 asking executives how decisions were made in their industry on the continuum between either being more reliant on human judgement or more dependent on computer models. The most algorithm-driven (and data-driven) industry was, not too surprisingly, Insurance, with Industrial Products and Technology tied in second place. At the other end of the spectrum, and the reason for this piece, was the Asset Management industry: of all 13 industries surveyed, Asset Management was far and away the most reliant on judgement and the least informed by computer models.

That’s a remarkable finding. In other words, decision-making in the Asset Management industry is more based on “old-fashioned” human judgement and less informed by computer models and algorithms than twelve other “industries” including Communications, Automotive, Healthcare, Energy, Retail, Banking, Technology, and (shockingly) even Government.

To be more reliant on judgement and less on models is also to be generally more subject to emotion. Much is said about the problem of emotion in the realm of investment decisions. Most identify two primary offending emotions that get in the way of good investment decisions: fear and greed. It might actually be simpler than that – the sole problem may be fear manifesting itself in two ways: fear of loss and fear of “missing out”! Obviously, those two sides of fear operate in different environments. Fear of loss is strongest in bear markets. And fear of missing out rears its head when markets (or sectors industries or certain IPOs or stocks) have been unusually strong.

This is the source of opportunity. Overreliance on human judgement exposes one to all the damage that the human emotion of fear can wreak on a portfolio. And all that can be avoided by developing a sound, data-driven quantitative model for investment decisions and then exercising the discipline to stick with that process and not second-guess it. That is much easier said than done (at both ends), but it is still worth the effort.

Our process, as you know, is as quantitative as we can make it. That said, it is not and can never be devoid of all human judgement. Sometimes, there is no (or very little) data. More often, there is data, but in this rapidly changing world something material may have changed rendering the data irrelevant or past relationships misleading so we must always apply judgement to the models.

This is not new for us – we have always taken as quantitative an approach to the investment process as we could for all the reasons detailed here. And we have often commented about that and about why that is beneficial. Perhaps you have read that and thought, “Sure, they say that, but surely, and logically, other firms must be pretty similar in that regard.” The PwC survey illustrated in the chart above speaks directly to that and the implication is clear: “Not so much.”