Inflation is a hot topic among our clients and has come up more in the last two months than the entire last decade! Whether it’s higher food costs at the grocery store (bananas!), the surge in used car prices, the cost of gasoline, etc., it’s obvious why inflation is on everyone’s mind today. In this article, we will delve into the recent inflation in more detail, but first let’s start with why inflation has been low until this year.

Why has inflation been low?

The Federal Reserve has long targeted annual consumer inflation of 2%. Yet since the Great Financial Crisis, the US Economy has had difficulty reaching price level increases of this pace until this year. Given the variables involved, analyzing economies is a very complex exercise. However, some emerging trends can explain lower average inflation over the last decade.

Globalization has played a significant role in keeping inflation low. Countries continued with their adoption of free market reforms and thus grown the available global labor pool. Companies have taken advantage of cheaper labor sources to reduce their costs and have competitively priced their products. Technology has also played an important role in every business. The growth in technology has increased productivity and reduces the need for new factories, equipment, and workers. This has potentially led to less overall demand for labor and ultimately inflation.

Why might inflation be picking up?

Consumer demand is strong, bolstered by stimulus, while production has not returned to pre-Covid levels causing some supply shortages. The Bureau of Labor Statistics started tracking total job openings the US Economies since 2000 (chart below). As you can see in the chart, there has recently been a huge jump in the number of job openings which hit an all-time high of 9.3 million recently. This surpasses the previous peak in late 2018 of 7.5 million job openings. Companies are competing to hire workers and are therefore raising wages. Many media outlets have reported about companies offering higher per hour wages and sometimes bonuses to attract applicants. When labor costs go up, businesses are forced to raise the price of products or services to maintain the same level of profit.

While wage and price increases are the visible indicators of inflation, many economists believe that it is the amount of money in circulation that leads to inflation. The actions the US Federal Reserve and Congress (and other countries) took to get through the pandemic have resulted in an increase in the money supply. Illustrated below is a chart of M2 for the US economy going back to 1959. M2 measures cash and checking deposits, along with “near money”, which includes things like money market funds and savings deposits. As is obvious in the chart, there has been a large increase in the money supply. On a percentage basis, this amounts to a 30% jump, the largest one-year move on record (with data only from 1959). Looking back at the 1970’s, a decade in which the US economy experienced higher than usual inflation, the M2 measure increased 150% in total, with the largest calendar year increase a little over 12%. This money supply increase is a big part of the reason so many people are more concerned about inflation today.

Is the inflation we are currently seeing “transitory” and how will we know?

Current Federal Reserve Chairman Jay Powell has argued the inflation we are seeing is “transitory”. The most recent Consumer Price Index (CPI) report (the bellwether inflation index) increased 5.4% year over year. It was the largest increase since August of 2008. The argument for this being a temporary rise in prices can be attributed to a few different factors. First, the low base effect. The second quarter of 2020 looked very different than today. We were in the early stages of the pandemic, consumer demand collapsed for some goods and services, and prices were depressed. Thus, it seems intuitive that prices today would be meaningfully higher on a percentage basis when compared to the depressed level of a year ago. Second, there are shortages of a variety of goods. The supply side has been constrained, mostly from the labor shortages mentioned above. Third, there has been more spending on goods. Due to the pandemic, people have shifted spending patterns from services and vacations to goods, which are a bigger component of the CPI.

Monetary economist Milton Friedman, who was known for his inflation research, believed “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output”. He also acknowledged that inflation took a while to manifest itself. Typically, this was two years from the actual increase in the money supply, as he concluded that for inflation to be more permanent, it must eventually show up in wages. Wages aren’t like products on the grocery shelf. They take more time to adjust, and they only tend to rise rather than to fluctuate. For example, most union contracts aren’t negotiated annually and have a duration of several years. It is difficult for consumer price inflation to persist without wage inflation, since higher prices cause affordability issues absent a corresponding increase in wages.

Beyond the supply of money, the speed at which it is exchanged, known as velocity, also plays a role in inflation. Velocity is defined as how many times a unit of currency is used to purchase goods and services in a given year. Milton Friedman assumed that the velocity of money is constant, and that was a reasonable conclusion during his time. However, the decline in the velocity of money has confounded economists since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. It is a variable in an important equation: Money Supply x Velocity = Price Level x Real GDP. Below is a chart of the velocity of money since 1959:

As you can see in the chart, velocity has declined from about 1.9 in 2007 to 1.12 at the end of 2020. Even though the money supply has increased substantially over the last year, a drop in velocity can potentially offset some of the inflationary pressure.

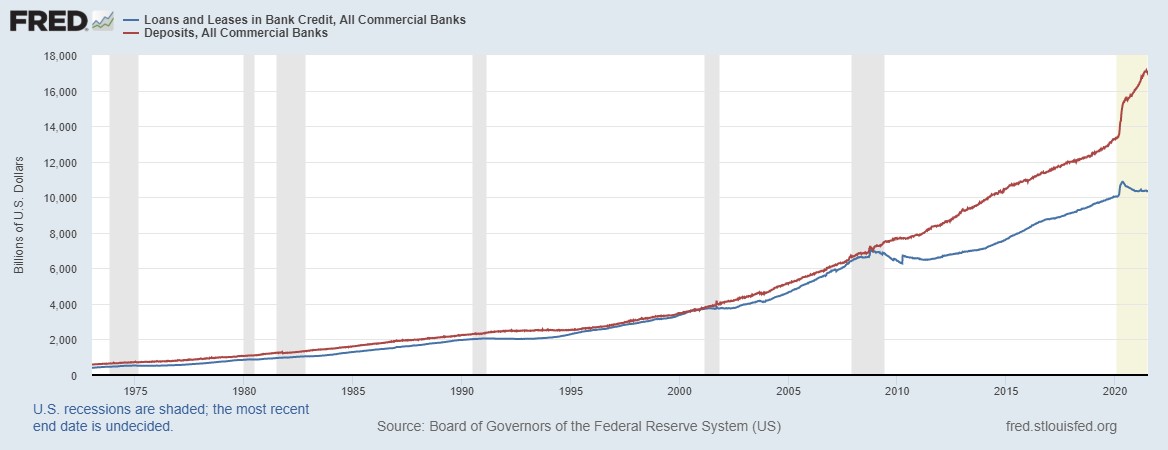

Reduced bank lending is a significant factor in the decline of money velocity. Private banks are the backbone of the financial system, and unlike the Federal Reserve, can increase the money supply through lending. The red line in the chart below represents deposits at all commercial banks. The blue line is the amount of loans outstanding. Most recently, loans were about 60% of total bank deposits, which is a record low for the data set. This is a key component of the inflation question. In order for inflation to persist, it’s likely loans would need to increase relative to deposits, which would drive a higher velocity of money.

How does inflation impact Bonds, Stocks, and Real Estate?

Warren Buffett once described inflation as a financial tax. Investors seek to earn real returns. Real returns are what an investor is left with after inflation is subtracted from the nominal total return. For bonds, the nominal interest payment can be broken down into two components: the real cost of funds plus the expected inflation rate. As inflation expectations rise, so too should interest rates, which means the price of bonds will fall.

Higher interest rates create competition for stock investments, which puts pressure on stock prices. However, over longer periods, companies can pass on increased costs through raising prices to customers to protect their profits and allow stocks in aggregate to mitigate inflation.

Investment real estate is considered a good inflation hedge, because rents can ultimately rise faster in an inflationary environment. Real estate is a tangible asset whose value is derived from its replacement cost. If inflation causes the cost of new construction to increase, the value of existing properties will also rise.

We believe inflation is a concern, and some of the inflation we are experiencing could prove to be more permanent than transitory. With today’s traditional fixed income investments providing lower yields at longer maturities, we continue to focus on shifting our allocation to alternative credit which offers higher yields without lengthy maturities. In stocks, our approach leans towards value and focuses on companies trading at reasonable multiples which often pay dividends that are growing. Value stocks tend to be less impacted by rising interest rates. Our dedicated real estate is comprised of equity investments in real estate, whether public or private, is one of the best hedges against inflation. Lastly, we also have a dedicated allocation in portfolios to inflation-protection bonds which are the most direct inflation hedges because inflation comprises a portion of their return.

To listen to an episode of our podcast about this same topic, click here.