“No, that is the great fallacy: the wisdom of old men. They do not grow wise. They grow careful.”

― Ernest Hemingway, A Farewell to Arms

“How did you go bankrupt? Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

― Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises 1

2024 was an unusual year in many ways, including in politics and markets. It included the withdrawal of one presidential candidate after the primary elections, and two unsuccessful assassination attempts of another candidate. Tight polls fostered widespread expectations of a close election and a drawn-out vote-counting process. Then, in yet another surprise, the November elections were essentially decided in a day. Whether delighted or dismayed by the several outcomes, nearly all celebrated the vote count order and brevity, and markets reacted with at least relief for the quick resolution. Significant reduction of political uncertainty, avoidance of a feared undecided election, and an expectation of a more business-friendly administration combined to boost US stocks by 5.7% in November before correcting some in December. Small fourth-quarter gains for stocks added to significant market advances in the first three quarters. Consumer Confidence, investor confidence, investment advisor confidence, and CEO Confidence all initially rose post-election.

Moreover, the S&P 500’s total return in 2024 of 25% followed 26% gains in 2023. 25% or better market returns in back-to-back years is uncommon, having occurred only 3 other times in the past 100 years, the last one 26 years ago (1997-1998). How many of those were followed by a third 25%+ year? None. One was very good (+21%), one was middling (+6.6%), and one was quite bad (-35%). It’s a mixed bag and a tiny sample, but a third year of 25%+ returns in 2025 would be unprecedented in at least the last 100 years.

Still, market optimism abounds. The economy continues to expand at a good pace, and many expect the new Administration and Congress to ease substantial regulatory overhead and preserve investor-friendly and income-producer-friendly current tax rates (widely referred to as the anticipated tax “cuts”.) And in case you haven’t heard: a momentous AI-driven productivity boom is nigh at hand. What’s not to love?!

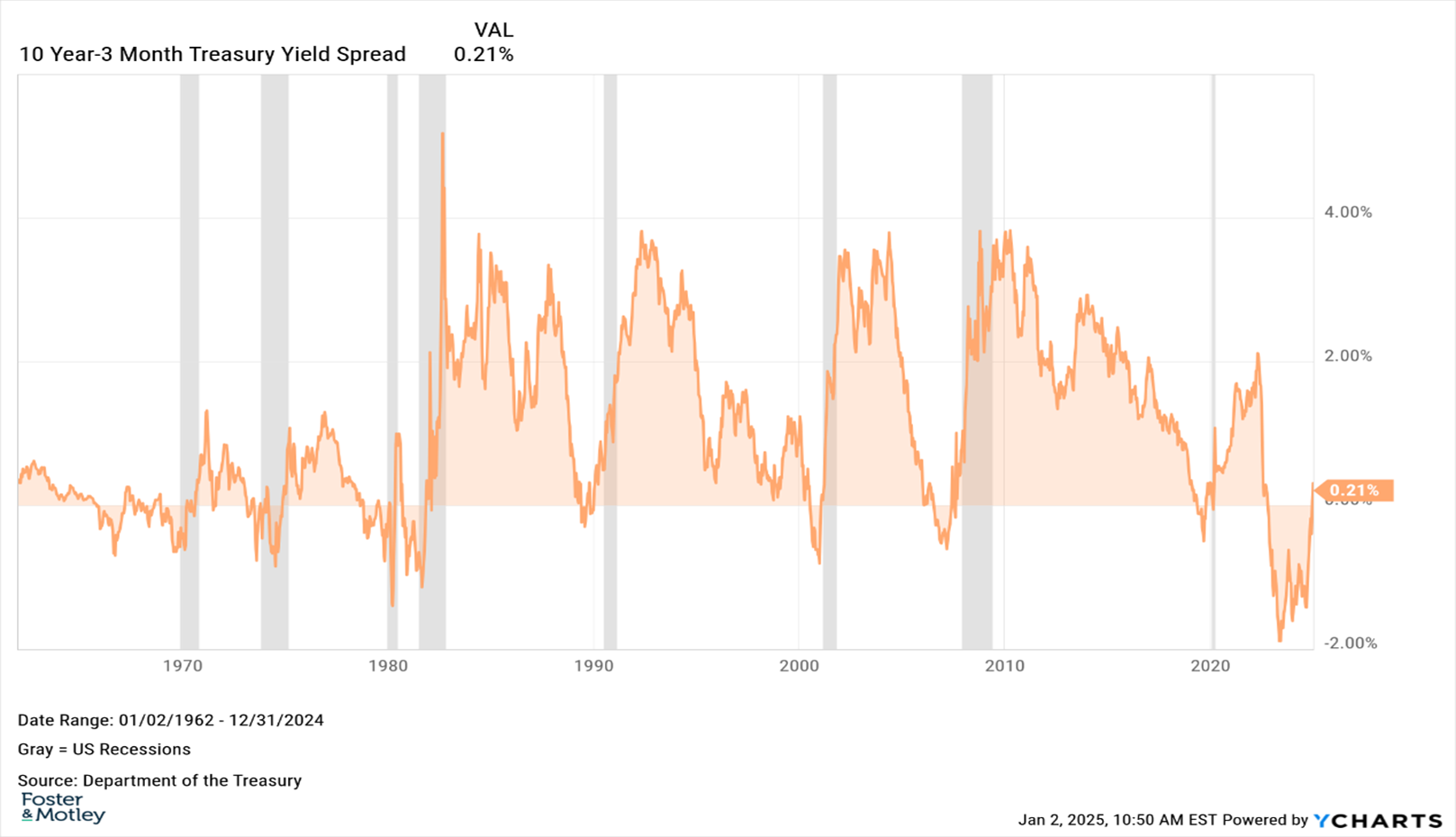

Recession omens, for one. Unemployment by one important measure (the “Sahm Rule”) is flashing a clear recession signal. After the US unemployment rate fell fairly consistently for several years to 3.5% shortly before COVID and rocketed to 14.8% in April 2020, unemployment fell to 3.4% in April last year. Then it climbed 0.6% to 4.2% with the December report. An increase of 0.5% or more in the unemployment rate from a cyclical low has historically preceded a recession and triggers the “rule” forecast. Another troubling precursor of recession is the reversal of an “inverted” yield curve which just occurred in December.2

Two indicators with excellent track records for predicting recessions are currently raising concerns. Beyond that, market celebrations dial up our disquiet and reinforce natural defensive tendencies. In fact (with a nod to Dorothy Parker), we could even say that beyond Recession fears, four are the issues about which we fret: tariffs, market ebullience, inflation, and debt.

The telegraphed tariff regime could pressure economic growth, and corporate earnings while feeding inflation. That said, we feared the same in 2016-2017 while the economy and markets absorbed those tariffs and lots of trade war saber-rattling with ease, scarcely missing a beat. We hope tariff concerns are equally misplaced this time.

As to market valuations, there are many ways to assess valuation, but most put the S&P 500 Index in the top 5-10% of its historical valuation range over the past 35 years. For example, the S&P 500 “forward” price to earnings ratio (i.e., the index divided by 2025 earnings estimates), is in the top 5% of its historical range since 1990. Very high valuations say a lot about likely long-term stock returns from here (expect lower than average), but little about the prospect for returns over the next year. However, valuations this extended leave little room for near-term disappointment, raising risks of larger adverse market swings in the event of economic shortfalls or negative geopolitical surprises.

The December Consumer Price Index (CPI) report showed consumer inflation of 2.7% over the prior year, while ex-energy and food “core inflation” was higher at 3.3%. Producer prices rose 3.0% in the latest year, and 3.4% ex-energy and food. Inflation at such levels isn’t rampant, yet it remains sufficiently above the Fed’s 2% target to call into question continued interest rate cuts by the Fed.

As noted, the election season included nearly every twist and turn imaginable (and some beyond). Yet one thing conspicuously absent was meaningful discussion by either party of the ballooning Federal Debt, which now exceeds 120% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Debt binges typically lead to undesirable consequences … eventually. But the likelihood of repercussion is exceeded by the uncertainty of its timing. That makes impractical protection against market swoons other than generally leaning into care and caution in portfolios. But paying down the Federal debt is all but impossible, and default is unthinkable, which leaves shrinking it through slow devaluation as the most likely outcome – i.e., inflation. Independent of what happens to inflation in the near term, rapid growth in the federal debt increases the risk of long-term higher inflation, which, among other things, would be a drag on long-term after-inflation returns. So increased portfolio protection against higher potential long-term inflation seems to be in order.

Moreover, Federal debt comes from Federal deficit spending, and Federal spending above Federal revenues is running at the highest percent of GDP ever outside of war (WWII) or crisis (COVID). If it persists, it will likely continue to be monetized, fueling inflation and upsetting markets. If, on the other hand, Musk et al succeed at meaningful fiscal restraint, that could be a large near-term drag on the economy, with adverse effects on markets. There was little choice during COVID but for the Federal government to significantly increase deficits. However, the deficits never came down after the crisis waned and now it appears we are on a knife-edge with very little room for error in either direction. Deficits are fiscal stimulus and boost the economy and markets in the short run, but they also increase risks.

Concerns about debt, inflation, economic growth, and market valuations are amplified by the market’s narrowness, which we’ve referenced multiple times recently. The top five stocks in the S&P 500 Index currently account for an astounding 28.7% of that index – if we managed a portfolio with such high concentration, we would not consider it adequately diversified, and you likely wouldn't either. In 2024, expensive stocks greatly outperformed cheap stocks, and by even larger margins large stocks outperformed small stocks, and US stocks outperformed international stocks. This means diversification, the very thing that should help most the next time the market takes a tumble, was penalized in 2024. In addition to narrow markets, we are seeing rising long-term interest rates: From just mid-September through early January as we write this, the 10-year Treasury yield has jumped up a full percentage point from 3.62% to 4.62% - a development stocks seem to have ignored.

The turn of a New Year is a time for well wishes and optimism. Markets have certainly been ebullient, and we would prefer to be more positive and mirror market tone. But debt piles up, sticky inflation persists in the short term, economic growth may be showing some signs of faltering, and the stock market hit multiple new highs in 2024. When markets go up, they always do so “climbing a wall of worry”, and not all worries pan out. We hope that proves to be the case this time. But exceptionally high stock market valuations compel us to embrace as much caution as reasonable limits admit. As you know, caution for us doesn’t typically mean market timing. But it does mean very broad diversification, a higher focus on quality, and generally holding full target allocations of cash.

1 Two quotes from “Papa” in one epigraph?! I binged on Hemmingway last year.

2 Most of the time, longer bonds yield more than shorter bonds. Occasionally that flips and becomes “inverted”. We measure that by the difference between the 10-year Treasury note and the 3-month Treasury Bill. There have been eight recessions since 1970, and each was preceded by a yield curve inversion. Most recessions were also preceded by a yield curve reversion, i.e., by longer interest rates exceeding short-term rates again. Here’s the history graphed:

You can see that the ending of yield curve inversions is nearer to the onset of recessions than the beginning of inversions. Inverted yield curves ended between 6 months in advance of the onset of recession to 8 months after, with the average being about 1 month after. Note also that the official recession start and end dates come from NBER and those points are typically declared one or two quarters after the fact.