Our standard interval for market comments is quarterly. Yet, when volatility jumps, as it did in 2020 during the early weeks of the COVID crisis, we may supplement that frequency. Although we just published a comment last Tuesday, the subsequent spike in market volatility since then cries for another.

Last Thursday and Friday, the S&P 500 Index fell 10.5%, its fifth-worst 2-day run since WWII.

We suggested the correction that occurred late in mid-March may have been largely driven by the intersection of high market valuation and new evidence of weaker economic growth. However, the subsequent volatility spike is all about tariffs.

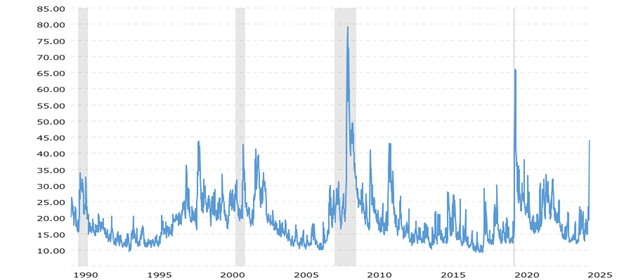

The Chicago Board of Options Exchange Volatility Index, commonly called the VIX, measures market volatility implied by option prices on the S&P 500. It was created in 1990, and this is its entire history through Friday:

Source: Macrotrends: https://www.macrotrends.net/2603/vix-volatility-index-historical-chart

This morning, the VIX index opened at 60.13. At a glance, it can be seen that 1) market volatility experiences massive “spikes” from time to time, and 2) at 60, this one is in the top three in the last 35 years (though, 1987 and perhaps 1974 would have also been up there had this index existed then).

This kind of unhinged market behavior occurs sometimes as a normal part of stock investing.

Yes, but: this time is different, isn’t it? This time is an unprecedented upheaval in global trade, a sudden, all-out trade war, a colossal unforced policy mistake. Doesn’t that make this one different, unique?

Of course it does. And so were each of the others – each one was unlike any others. In 2020, we had the global pandemic. In 2012, it was a European banking crisis. 2008-2009 was the mortgage crisis and Great Recession. 2001-2 were the financial accounting scandals of Enron, Worldcom, Global Crossing, etc. 1998 and 1999 each saw unique currency crises. Each one of those was unprecedented. Each was high drama, filling the news in its day, and each looked to have no end if you listened to that. But what happened? Each one passed. Each one eventually represented a great buying opportunity for stocks. And for each one, the point of maximum pain and angst represented the best opportunity.

Volatility spikes are, by definition, sudden affairs, and after Volatility peaks at 30, 45, 60, or whatever, it comes down pretty quickly. Peak volatility doesn’t always occur right at the market bottom – sometimes the market bottom occurs a little after. Yet peak market volatility always occurs nearer to the eventual bottom than to the prior peak. History is clear: unusually high levels of market volatility (and a VIX at 60 certainly counts!) should be viewed as buying rather than selling opportunities.

Uncertainty and occasional market downdrafts – even sudden and large – cannot be avoided or anticipated. So, Foster & Motley doesn’t attempt to predict the unpredictable. Instead, we build portfolios designed to survive such uncertainty without permanent damage. The only permanent portfolio damage is that which follows from bailing out after a historic market decline (which, fortunately, very few clients have historically done.)

We’ll likely see more drama before this one passes, but this one, too, will pass eventually. Until it does, the best course is to remain a long-term investor and avoid the temptation to fiddle with “market timing”. Stocks have been the great long-term wealth generator, and nothing in this new volatility eruption has changed that.